Christmas

lights are a big part of the holiday season. As November and

December roll around, you might see strands of lights everywhere

-- on Christmas trees, houses, shrubs, bushes and even the

occasional car! Have you ever wondered how these lights work?

Why is it that if you pull out or break one of the bulbs,

the whole strand of lights goes out? And how do they create

the lights that sequence in different color patterns?

In

this article, we'll look at Christmas lights so you can understand

everything about them!

Christmas

Past

If you were to go back in time 30 or 40 years and look at

how people decorated their houses and trees with lights, you

would find that most people used small 120-volt incandescent

bulbs. Each bulb was a 5- or 10-watt bulb like the bulb you

find in a night light. You can still find strands of these

bulbs today, but they aren't very common anymore for three

reasons:

- They

consume a lot of power .

If you have a strand of 50 5-watt bulbs, the strand consumes

250 watts! Consider that most people need two or three strands

to do a tree and five or 10 strands to do a house and you

are talking about a lot of power!

- Because

the bulbs consume so much power, they generate a

lot of heat . When used indoors, three strands

at 250 watts per strand are generating as much heat as a

750-watt space heater! The heat from the individual bulbs

can also melt things.

- They

are expensive .

You can buy a 10-pack of miniature bulbs for about a dollar

this year. The large bulbs might cost five to 10 times more.

The

one advantage of this arrangement is that a bulb failure has

absolutely no impact on the rest of the bulbs. That's because

a 120-volt bulb system places the bulbs in parallel

, like this:

You

can have two, 20 or 200 bulbs in a strand that is wired in

parallel. The only limit is the amount of current

that the two wires can carry.

Mini-lights

The 1970s saw a revolution in decorative lighting: Mini-lights

were introduced. They now dominate the market when

it comes to strands of lights. A mini-light is a small, 2.5-volt

incandescent bulb that looks like this:

Standard

mini-light bulb

|

Mini-lights

in a typical strand as you buy them in the store

|

These

bulbs are not much different from any incandescent flashlight

bulb (see below for details).

Given

that you are plugging these 2.5-volt mini-lights into a 120-volt

outlet, the obvious question is, "How can that work?"

The

key to using these small, low-voltage bulbs with normal house

current is to connect them in series . If

you multiply 2.5 volts by 48, you get 120 volts, and originally,

that's how many bulbs the strands had. A typical strand today

adds two more bulbs so that there are 50 lights in the strand

-- a nice round number. Adding the two extras dims the set

imperceptibly, so it doesn't matter. The lights in a 50-bulb

strand are wired like this:

You

can now see why mini-light strands are so sensitive to the

removal of one bulb. It breaks the circuit ,

so none of the bulbs can light! When mini-lights were first

introduced, any bulb burning out would darken the entire strand.

Today, the bulbs can burn out and the strand will stay lit,

but if you pop one of the bulbs out of its socket, the whole

strand will go dark. This difference in behavior occurs because

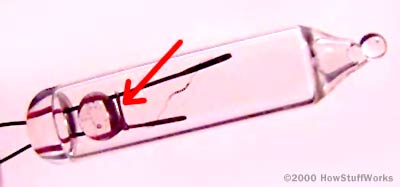

the new bulbs contain an internal shunt ,

as shown here:

Today's

standard mini-light bulbs contain a shunt wire below

the filament. If the filament burns out, the shunt activates

and keeps current running through the bulb so that the

rest of the strand stays lit.

|

If

you look closely at a bulb, you can see the shunt wire wrapped

around the two posts inside the bulb. The shunt wire contains

a coating that gives it fairly high resistance

until the filament fails. At that point, heat caused by current

flowing through the shunt burns off the coating and reduces

the shunt's resistance. (A typical bulb has a resistance of

7 to 8 ohms through the filament and 2 to 3 ohms through the

shunt once the coating burns off.)

Although

you can buy simple 50-bulb strands like the one shown above,

it is more common to see 100- or 150-bulb strands. These strands

are simply two or three 50-bulb stands in parallel, like this:

If

you remove one of the bulbs, its 50-bulb strand will go out,

but the remaining strands will be unaffected. If you look

at a strand wired like this, you will see that there is a

third wire running along the strand, either

from the plug or from the first bulb. This wire provides the

parallel connection down the line.

The

big advantages of mini-bulb strands are the low wattage

(about 25 watts per 50-bulb strand) and the low

cost (the bulbs, sockets and wire are all much less

expensive than a 120-volt parallel system). The big disadvantage

is the problem of loose bulbs . Unless there

is a shunt in the socket, a loose bulb will cause the whole

50-bulb strand to fail. It's not hard to have a loose bulb

because the sockets are pretty flimsy. There are testers on

the market now that can help find loose bulbs faster, and

they only cost $3 to $4.

Blinking

There are two different techniques that are used to create

blinking lights. One is crude and the other is sophisticated.

The

crude method involves the installation of a special blinker

bulb at any position in the strand. A typical blinker

bulb is shown here:

The

extra piece of metal at the top is a bi-metallic strip

. The current runs from the strip to the post to

light the filament. When the filament gets hot, it causes

the strip to bend, breaking the current and extinguishing

the bulb. As the strip cools, it bends back, reconnects the

post and re-lights the filament so the cycle repeats. Whenever

this blinker bulb is not lit, the rest of the strand is not

getting power, so the entire strand blinks in unison. Obviously,

these bulbs don't have a shunt (if they did, the rest of the

strand would not blink), so when the blinker bulb burns out,

the rest of the strand will not light until the blinker bulb

is replaced.

The

more sophisticated light sets now come with 16-function

controllers that can run the lights in all sorts

of interesting patterns. In these systems, you typically find

a controller box that is driving four separate strands of

mini-bulbs. The four strands are interleaved

rather than being one-after-the-other. If you ever take one

of the controller boxes apart, you will find it is very simple.

It contains an integrated circuit and four transistors or

triacs -- one to drive each strand. The integrated circuit

simply turns on a triac to light one of the four strands.

By sequencing the triacs appropriately, you can create all

kinds of effects!

Source:

How Stuff Works, Inc http://www.howstuffworks.com/

|